Inside the global jihad

Will Al Qaeda regenerate itself following Osama bin Laden's death?

By Bruce T. Murray

Author, Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

Searching for metaphors

During the George W. Bush administration's “War on Terror,” government officials often likened Al Qaeda to snake, which can be killed by cutting off its head. Al Quaeda has also been likened to the mythical hydra, a monster with multiple heads: Chop off one head, and two more pop out.

– Steven Simon

“These zoomorphic images are very revealing about the way in which people deal with the situation,” said Steven Simon, Senior Fellow for Middle Eastern Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Simon noted the drawbacks of the “snake” metaphor: Despite the fact that many Al Qaeda leaders were killed or captured in the years immediately following the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, terrorist strikes continued throughout the world – including London, Bali and Mumbai.

“Since Sept. 11, this movement has been under unrelenting coordinated international pressure,” Simon said. “Yet, in that time, they have attacked planes with surface-to-air missiles; they have attacked trains and gated compounds; they have launched audacious conspiracies to attack American embassies and consulates; they have experimented with toxins; they've carried out assassinations; and they embarked on a very audacious campaign to challenge American control in Iraq.

“And this is all being conducted by a group that is being chased all over the world and their leaders are being captured and killed. On a tactical level, you have to give them some credit.”

In developing a better metaphor for Al Qaeda, Simon suggests shifting from the reptilian kingdom to the fungi: “If on the other hand you don't believe it's like a snake, but more like a deadly mold, you might get a better sense of the difficulty in developing strategy to deal with it.”

Simon examines the origins of Al Qaeda and other Islamic extremist groups in his book, The Age of Sacred Terror, co-authored with Daniel Benjamin. The book explores the historical underpinnings of these groups – and the individuals behind them.

“The phenomenon represented by this group [Al Qaeda] is very complex,” Simon said. “It's important to recognize the complexity of this phenomenon to understand why it's so difficult to counter, let alone defeat.”

Tapping into minds

To a Western audience, Osama bin Laden's periodic broadcasts from his caves and rocky outcroppings might have appeared as the ravings of an eccentric madman, or perhaps a small glimpse of a psychotic mass-murderer.

But to a Muslim audience, even those who condemn bin Laden's actions, bin Laden's words and representations struck another chord:

– Steven Simon

“Bin Laden rather ingeniously manipulated images that are embedded in the Muslim consciousness,” Simon said. The Al Qaeda leader touched the Muslim consciousness by invoking the Prophet Mohammed's experience, the Koran and the historical experience of the Muslim world.

“Bin Laden was a megalomaniac who self-aggrandized himself, but there was also a self-effacing side: He dressed in simple clothes and simple military garb. He did not partake in any pleasures which he could have if he had chosen to remain with his family and keep his Saudi citizenship,” Simon said.

Bin Laden and the Muslim narrative

Osama

bin Laden was a very effective propagandist for the audience he was addressing, Simon said. Bin Laden evoked the image of the murabitoun,

or vigilant warriors, of the early the history of Islam.

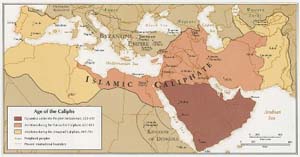

“As the Islamic empire was expanding [in the seventh and eighth centuries],

young men would flock to the frontiers of the empire, man the outposts,

push forward the borders of Islam and fight against those would encroach

on lands that had been won for God. These are powerful images, and bin

Laden manipulated them quite well,” Simon said.

Bin Laden frequently talked about the Crusades, which he brought to present times with what he referred to as the “Zionist-Crusader Alliance” between Israel and the United States. In his first statement after the bombing of the World Trade Center, bin Laden referred to the loss of Andalusia in southern Spain during the final push of the Spanish reconquest in the 15th century.

“The Crusades were a twofold experience for Muslims: They learned the bitterness and humiliation of defeat, but later the triumph of victory when Saladin defeated the Frankish defenders of Jerusalem,” Simon said. “These images are very powerful in the minds of Muslims. They are part of the larger template that influences the way in which current realities are assimilated and understood.”

On the other hand, Simon cautioned against stereotypes: “There is no single, unitary Muslim. Muslims of the world are differentiated by country of origin, ethnicity, tribe, profession, interests, and gender. But there are motifs that are familiar to most Muslims that are part of their narrative,” he said.

The extremist spin

Al Qaeda and other extremist groups weave certain themes into their statements and propaganda. Among them:

- War of religion and economics – In his audio tapes,

bin Laden tied these two elements together.

“He created an umbrella under which many local movements form cover. That's how the movement grows and achieves its protean character,” Simon said. “The economic piece is classic anti-colonial rhetoric: ‘Westerners have come and taken our oil; ripped us off; and used us for their own economic gain.' It's standard neo-Marxist rhetoric, combined with other motifs to broaden the appeal.”

- Jihad against the Jews and “Crusaders” – Israel

must be destroyed and Jews and their American allies must be killed

wherever they are, according to Osama bin Laden's 1998 fatwa.

- Apocalypse now – Al Qaeda and other radical Muslim organizations

have well-developed apocalyptic literature that they disseminate on

the world wide web and in pamphlets.

“Apocalyptic political literature talks about weapons of mass destruction as a way to end history,” Simon said. “In these stories you find Armageddon-type imagery – the final Muslim victory against NATO, the EU, the UN, Israel; and it finally ends when an Atomic bomb goes off in New York City, and the rest of the Americans convert to Islam.”

- Gnosticism – Gnostics believe we lack the capacity to

understand our true state of being. Such knowledge would enable us to

transcend our captivity in this world and escape into a more ethereal

realm, according to Simon.

“We are in a prison, but we don't know it. We are living in a big lie, and people are lying to us,” Simon said. “This is a tough mentality to go against; because if you present a peace process and a road map, the other side says it is all a lie, a ruse.”

Sin, expiation and sacrifice

Muslims are deeply concerned about sin and expiation (penance). “It's a sense that things are bad for Muslims, and that it is the fault of Muslims for letting it happen,” Simon said.

The most dramatic outgrowth of this kind of thinking is suicide bombing. Teenage boys are especially drawn to suicide bombing as a solution to sin and expiation.

“It is very appealing to adolescents. It's very compelling; it's very sexy, and very romantic. It becomes a fad,” Simon said. “These are vulnerable people. They are in between things: They are already men, but they are not married; they have finished school, but they are not working. It is precisely such people who are to be sacrificed because they are impure, and they are impure by virtue of their in-between-ness.”

Older people also commit suicide bombing. Even women have been recruited in recent years. Simon said it is important to distinguish the different motivations behind suicide bombing. For example, in October, 2003, a 29-year-old woman and law school graduate Hanadi Jaradat blew herself up at a restaurant in Haifa. Her brother and a cousin had been killed by Israeli defense forces

“This case seems to be explainable on the basis of some horrible things she had experienced. One can see a person like that saying, ‘What have I got to live for? I'm gong to end it all, and get those bastards at the same time,'” Simon said.

Jihad

The Age of Sacred Terror recounts the story of the Islamic reformer Taqiyy ad-Din Ahmad Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328). Ibn Taymiyya co-founded a law school and advocated a strict constructionist view of Islam.

“He contributed two important concepts to the debate at that time which resonate very strongly in the salafi movement, from which Al Qaeda emerged,” Simon said.

Ibn Taymiyya lived at a time when the Islamic world was suffering from external pressure and internal strife. He believed it is not enough to have a powerful ruler who can create stability, but it is also essential to have a righteous ruler.

“A key attribute of righteousness is the vigor by which a ruler implements Islamic law in his kingdom, and the vigor with which he carries Islam to the lands that lie outside the Muslim perimeter,” Simon said.

Ibn Taymiyya also advocated amending the five pillars of Islam, which are,

- Faith in the oneness of God and the finality of Mohammed's prophecy

- Daily prayers

- Charity

- Self-purification through fasting

- Pilgrimage to Mecca by those who are able

“Ibn Taymiyya asked, ‘Where is jihad in these

five pillars of Islam?' He looked at the prophet's life and

saw physical combat against the enemies of God was a key component of

his career. He thought it was inexplicable that jihad was not revered

in the same way as the other pillars of Islam,” Simon said.

“There never became six pillars of Islam, yet he set into motion

a train of thinking in Islam that placed jihad on the same level as the

other five pillars of the faith.”

Colonial oppression and reaction

By the time of the late 19th century, much of the Islamic world had come into the orbit of European imperial powers.

“Muslim intellectuals asked themselves how it was that Islam was in this condition and how easily the Muslim lands were occupied by these foreign powers,” Simon said. “Their answer was, ‘We have been untrue to our roots. If we try to recapture the values and practices of the early age of Islam, in its first two centuries of expansion and vibrancy; if we shake off centuries of dead commentary and constraints on thinking, we will be able to challenge our oppressors on equal terms.'

"Then Muslims would be in position to take from the West various advances, make them authentic in an Islamic way, and not only challenge the colonizers, but become better Muslims in the process.”

Before colonial times, clerics occupied an important place in Islamic societies. Under colonial administration, clerics were not considered useful from the standpoint of the colonial governments, which needed natives who could speak European languages and occupy administrative functions. The successor states that arose in the place of colonial governments similarly excluded clerics, and most became despotic military regimes.

In post-colonial Egypt, a radical movement emerged drawing from Ibn Taymiyya's ideas – that the secular authoritarian rulers were impious and did not deserve to be in power. In the 1970s an Egyptian electrical engineer named Abd al Salam Faraj wrote a book called “The Forgotten Obligation.” Drawing from Ibn Taymiyya, he advocated the sixth pillar of Islam, jihad. The book propelled an insurgency against Anwar Sadat's government (Sadat was assassinated in 1981), and later against the Mubarak government – which crushed the movement.

“The Egyptians who escaped the hammer and fist of Mubarak's secret police went to Afghanistan where they linked up with Saudis and formed Al Qaeda,” Simon said.

Jihad in Europe

A new field of jihad has emerged in Europe, with its high populations of unemployed, disaffected Muslims. Most of the radicals emerging from Europe are from third and fourth generation immigrants. (See discussion with Christopher Caldwell, “What is the West’s Problem with Islam?”)

“They don't speak the languages of their grandparents. In that sense they are completely assimilated. They speak French, Spanish, Italian, German, Dutch, Flemish and of course English. They don't speak Turkish, Urdu, Farsi or Arabic. They did not have systematic Islamic schooling. And they often view their parents' Islam as a washed-out set of boring rituals and empty usages with no meaning to them,” Simon said.

“They are excluded from the broader European society in which they live. They are simultaneously assimilated and alienated. They are looking for some identity to which they can hang on and give them some meaning. Islam provides this identity and sense of pride.”

What appeals most to the new converts is jihad.

“When I was interviewing Muslims in Britain, one line was particularly striking: ‘Why would I want to be Anglican? Have you ever seen an Anglican priest kill for his religion? No. What kind of religion is that?' The alternative is a robust religion that people will fight for and put their lives on the line for,” Simon said. “Sacrifice is a very powerful motivating factor.”

Simon has advocated affirmative action for Muslims in Europe as a way

to help integrate them in their host societies, but it is unlikely any

European government would adopt such a program

“Hell will freeze over before the French adopt affirmative action

for Muslims,” Simon said.

Tough nuts to crack

The Middle East and the Muslim world have various attributes that will make the problems there very difficult to solve in both the long and short-term. Among them:

- Hormonal time bomb – The recent news splash about the

16-year-old Palestinian boy who was about to conduct a suicide bombing,

then changed his mind at the last minute, raised awareness of the demographics

of the Middle East and the Muslim world, which is experiencing a “youth

bulge.” In some Muslim countries, 60 percent of population is below

the age of 16.

“Not only are we talking about a region that is undergoing very difficult economic times, but also a region composed mostly of adolescents. For anyone who has adolescent children, you know the difficulties involved,” Simon said.

- Distributed economies – The typical economic model for

Middle Eastern countries that have oil resources: The kings, emirs,

sultans or despots get all of their cash from oil. They don't need

to tax their subjects, because all of their money comes from the ground,

Simon said.

“Because there is no taxation, there is no representation. The government does not have to be transparent or accountable,” he said. “This is a difficult thing to break out of, because people don't like to be taxed.”

- Transitional hang-ups – In other parts of the world, such

as South America, democratic transitions often occur when a military

government is overthrown. In another way, democratization could come

about when reform-minded members of an existing regime work in tandem

with moderate oppositions.

“The reform minded members of these regimes hope to survive by convincing the oppositions that they can keep the secret police under control. This is part of a trust-building process that takes a long time to evolve,” Simon said. “But in the Middle East, the state is military, and the opposition is all Islamist, so they have a very hard time convincing people that they really want democracy.”

- Church state problems – The caliphate of early Islam was

the embodiment of church and state in harmony. “If you were the

caliph, you could count on the clergy to say the right thing; and you

could count on the people to listen to their clergymen,” Simon

said.

During colonial rule, the authority of clerics broke down; and the relationship between governments and religious leaders remains broken in most cases. In the Muslim world today, with the notable exception of Iran's theocracy, the clergy is neither an establishment of the government, such as the Greek Orthodox Church, nor a structured hierarchy, such as the Roman Catholic Church.

“It becomes problematic when you get an informal clergy informed by the radical tradition, such as the Wahabbis in Saudi Arabia; and governments that are viewed as illegitimate,” Simon said

Solutions

- Diplomacy – What kind of vocabulary will the U.S. employ?

“The United States is obsessed with religion,” Simon said. “The U.S. is arguably more religious now than it has ever been in its history. But as a government you don't conduct faith-based diplomacy: You don't use religious terminology; you don't advance our own religious narrative. You keep these things on a secular plane. But if the other side doesn't think that discourse is legitimate, unless you want to have the kind of dialogue in which two people are talking to themselves, you need to learn how to talk in terms of how the other side will listen.”

- Norms on war and violence – Simon stressed the need to

promulgate international laws regarding weapons of mass destruction

and inflicting mass casualties on civilians.

“We need to try to develop international norms to discredit mass casualty attacks, and do so in tandem with a debate in the Islamic community about the legitimacy of these attacks,” Simon said. “This is important because of the apocalyptic piece of the ideology. For some in the movement, weapons of mass destruction are tools of asymmetrical warfare – when you're up against a powerful enemy that has military superiority, you compensate with some extra firepower.”

- Democracy – Many experts believe introduction of democracy

in the Middle East and South Asia will take the wind out of the sails

of extremist groups by giving them representation.

“Moving in the direction of democracy would probably make things better, or at least shift some of the grievances, but this is an enormously difficult thing,” Simon said.

Some Persian Gulf countries are experimenting with democratization in the form of representative legislatures that are empowered to review the emirs' edicts. Gulf states are also moving toward universal suffrage – to include woman and Shiites. But no rulers in the region are directly elected.