The Historical Basis for the First Amendment

– Prof. Philip Goff

From Protestant pluralism to the Judeo-Christian tradition

By Bruce T. Murray

Author, Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

Translating diversity to liberty

The concepts of diversity and pluralism – discussed so much in public life today – meant something very different in 18th century America.

The original 13 colonies were inhabited almost entirely by Protestants, with their origins Great Britain and Western Europe. By today’s standards, the colonies would look homogeneous. Yet by the standards of the day, colonial America was quite diverse, and new Americans had to find a way to negotiate their differences.

“Most people believed basically the same thing. The problem was that small differences could become big,” said Philip Goff, professor of religious studies at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis. “But for the most part there was a belief in the intrinsic good of diversity in a Protestant context.”

The historical experience in early America paved the way for what has become the most diverse nation on earth, religious and otherwise.

Pluralism and religious establishments

Diversity and pluralism are similar but different: Diversity, at its most basic level, simply means heterogeneity – the existence of different types. Pluralism is a philosophical commitment to diversity, a belief that there is some intrinsic good in difference, Goff said.

In colonial America, diversity existed among the different colonies; but within the individual colonies, religious diversity was not the order of the day. In New England, with the exception of Rhode Island, the Congregationalist Church was the established church; while in Virginia, the Anglican Church was the official church.

Religious groups not belonging to the established church did exist in the colonies, but they “flew beneath the radar,” and their influence was minimized, Goff said.

The tradition of established churches followed the pattern of England and Europe, where churches were supported by the royal governments and their subjects. Similarly, in America the colonial governments taxed citizens to support the churches. Church and state were connected: In order to serve public office, one had to make a statement of faith in accordance with the established church.

“In the 1740s, if you were a Baptist in Virginia and you wanted to run for office, you couldn’t. You had to be a member of the Anglican Church,” Goff said.

In colonial New England, one had to be a member of the Congregationalist Church in order to hold public office. The laws didn’t come directly from the church, but the church was the gatekeeper for those who could get into government and make decisions.

The Middle Colonies – New York and Pennsylvania – accepted greater religious diversity and would later become important examples for religious liberty.

From revival to revolution

During the 1730s, the Great Awakening swept across the colonies. The Great Awakening was fueled by itinerant preachers, led by Jonathan Edwards and later George Whitefield, who traveled up and down the Atlantic Seaboard delivering their message.

The Great Awakening crossed denominational lines and drew people from all walks of life. The movement emphasized a life-changing religious experience – “the idea that you could point to a specific moment where you could say ‘I was changed by an emotional experience of grace,’” Goff said.

“There was a growing notion that in order for someone to get to heaven, you had to have this experience. That became paramount. Everything else seemed trivial after that. This resulted in cooperation among the Protestant groups, and from there pluralism began to develop.”

But the Great Awakening was not universally heralded. Established clergy

often resented the itinerant evangelists captivating and drawing away

their church members. Some congregations split along the lines of the

revivalists, called the “New

Lights” versus the “Old Lights” – the traditionalists.

“The Awakening, which signaled the advent of an encompassing evangelicalism in American life, invigorated even as it divided churches. The supporters of the Awakening and its evangelical thrust – Presbyterians, Baptists and Methodists – became the largest American Protestant denominations by the first decades of the nineteenth century. Opponents of the Awakening or those split by it – Anglicans, Quakers, and Congregationalists – were left behind,” according to a Library of Congress historical summary.

According to Goff, the experience of the Great Awakening tied the colonies together, created a sense of unity and fostered cooperation. For this reason, many historians believe the Great Awakening helped lay the groundwork for the American Revolution.

“Many Christian Americans believed that the colonies were a New Israel and that the colonists were God’s chosen people, views that steadily hardened defiance of the established royal governments and the ancient tradition of the divine right of kings,” according to a summary of Christine Leigh Heyrman's The First Great Awakening. “For these Americans, the rebellion became a holy war against Britain and her king, who were viewed as sinful, corrupt.”

See more on religion and the American Revolution here.

Separating church from state

– Philip Goff

From the time of the American Revolution through the creation of the Constitution, a broad consensus emerged regarding the benefits of “disestablishment,” or the separation of church and state.

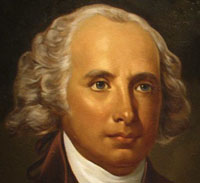

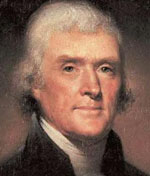

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison both argued against an established state religion. They emphasized how religious establishments corrupted government. Another statesman, Isaac Backus, a Baptist, argued for separation from a religious point of view. Backus believed that mandatory membership in a church corrupted both the individual and the church.

“No man can become a member of a truly religious society without his own consent; and also no corporation that is not a religious society (i.e., the government) can have a right to govern in religious matters,” Backus wrote in his 1783 tract, “A Door Opened to Christian Liberty.”

Other statesmen, including Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee, advocated making Christianity the official religion, regardless of denomination. Madison argued against this idea. Giving government the right to say “as long as it is Christian” already cedes it power to say “a certain type Christian,” Goff said.

Madison’s 1785 treatise, Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, provided a powerful argument against any entanglement of religion and the state.

“The religion of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an unalienable right,” Madison argued.

Goff expounded on the point: “The Founding Fathers looked at liberty as unalienable: It can’t be given; it can’t be transferred; it can’t be taken away. It is a natural right. Religious liberty was a guarantee through the right of nature to choose – to choose to be different or to chose to be the same – whatever the choice might be.”

Madison was instrumental in the drafting of the First Amendment and the language of Article VI of the Constitution, which states “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.”

Madison and Jefferson are both associated with a movement popular in the 18th century known as Deism. Deists believe in the existence of God or a supreme being, but deny revealed religion, such as biblical texts. Instead, deists base their belief on reason and nature. The Declaration of Independence, penned by Jefferson, displays flashes of Jefferson’s deism with his reference to “the laws of nature and of nature’s God.”

Goff explained how Deists were inclined toward separation of church and state: “The Deists and evangelicals both agreed that it made better sense to guard your own conscience and guard your own church by not having an overlapping church and state,” he said. “If you separate the two, you actually help the church because you don’t sully it with politics, and you also do your own conscience better because you don’t have to say you believe in X, Y and Z to hold office.”

From First Amendment to Fourteenth Amendment

– The First Amendment, Religious Liberty Clauses

The first 10 words of the First Amendment form the Establishment Clause; the following six words form the Free Exercise Clause. Together, all 16 words constitute the Religious Liberty Clauses.

The Establishment Clause was originally intended to prevent the new federal government from declaring an official church of the United States, “but state governments could still do their own thing, and continued to do so after the Revolution, especially in New England,” Goff said.

Not only the Establishment Clause, but the first 10 amendments to the Constitution initially applied only to the federal government. After the Civil War, Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment, primarily to guarantee rights to former slaves. The Fourteenth Amendment had many further ramifications, among them making most of the Bill of Rights apply to states through a judicial process known as “incorporation.”

Goff explained the rationale for incorporating the Religious Liberty Clauses: “If the federal government is going to establish certain rights, including that government cannot prohibit free exercise of religion, then a state cannot be allowed to do it either,” he said.

From that idea, for example, it would be unconstitutional for local school officials to sanction prayers before class or football games, since public schools are a function of the state and funded by the state.

Despite this “wall of separation” between church and state, total separation is still impossible. Like the early Puritan settlers in New England, the people who serve the government today hold their own religious values and beliefs; and people make decisions informed by their beliefs.

“You can separate religion from public events like football games; but you’re still dealing with individuals who make moral decisions and decide how they are going to vote based on religious reflection,” Goff said.

Religious free market

Goff said the First Amendment has resulted in a kind of “free market” for religion.

“In the free market, there is competition,” he said. “How do you market yourself as a church? So do you advertise? How do you appeal to certain people?”

The conservative and evangelical churches that are showing the most growth are doing the best job at marketing themselves, Goff said. But just like any free market, religion becomes part of the larger market of culture, including the political culture.

“In politics, where leaders are constantly trying to cajole opinion in their direction, this is part of the language of God and country,” Goff said. “You can sell people on your opinion by using just the right sort of religious language. This is easy when it’s just God and country. It becomes more complex when it becomes ‘my version of God and country.’ This is where the cultural wars are fought.”

In such an atmosphere, pluralism and acceptance of differences can easily be lost.

“In a moment of crisis, when people are pushing a particular view of God and a particular version of country, you’re less likely to celebrate a different view,” Goff said.

Diversity in the 20th century and beyond

With the huge wave of immigration in the early 1900s, American Protestants

increasingly had to share their place with other religious groups, particularly Catholics and Jews.

With the huge wave of immigration in the early 1900s, American Protestants

increasingly had to share their place with other religious groups, particularly Catholics and Jews.

“Protestant pluralism grew into a ‘Christian pluralism’ with more cooperation between Protestants and Catholics – part of which arose during World War II when Protestants served alongside Catholics; and services at the front were conducted by Catholic priests; and when the only Christian minister was a Catholic minister,” Goff said.

In the 1950s, Judaism became more accepted in the mainstream, largely because of the Cold War, and the struggle against an atheistic ideology, Goff said.

“You had to present a united front against godless communism,” he said. “And popular culture helped mainstream Judaism through movies like The Ten Commandments. ... What began as Protestant pluralism, over time becomes Christian pluralism, to ‘Judeo-Christian.’”

The balance further tilted further away from the old Protestant order with the Immigration Act of 1965, which opened the country to a more diverse group of new Americans than ever, especially Asians and Hispanics.

The changing demographic landscape is an ongoing news story. What does this ever-increasing diversity mean to Americans' religious notions of their country? What will America become? How will Americans cooperate and resolve their differences across broad lines of religion and ethnicity?

See further discussion of this issue in the article, Faith and Conscience in America, with Charles Haynes of the First Amendment Center.

Appendix – The First Amendment

Free Exercise Clause applies to states

– Prof. Philip Goff

In 1940, the Supreme Court “incorporated” the First Amendment's free exercise clause in the case of Cantwell v. Connecticut. Heretofore, the clause applied only to the federal government and not the states. Thus, for the first time, the Court applied the Fourteenth Amendment to an issue involving the free exercise of religion.

In Cantwell, the city of New Haven, via a state statute, attempted to prevent three Jehovah’s Witnesses from playing a record of a sermon on the street. The Court declared that the state statute, which required religious groups to obtain a permit for such activity, was unconstitutional.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses have done more to define and redefine religious freedom in the United States than any other group because of their challenges to state laws,” Goff said. “The First Amendment is like a piñata: The more you beat it, the more good things fall out.”

Establishment Clause applies to states

The Supreme Court incorporated the Establishment Clause in the landmark 1947 case, Everson v. Board of Education of the Township of Ewing. See more discussion of Everson here.

Appendix – The Great Awakening

Beginning of evangelical movement in America

“Toward mid-century the country experienced its first major religious revival. The Great Awakening swept the English-speaking world, as religious energy vibrated between England, Wales, Scotland and the American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. In America, the Awakening signaled the advent of an encompassing evangelicalism – the belief that the essence of religious experience was the "new birth," inspired by the preaching of the Word. It invigorated even as it divided churches.”

— From the Library of Congress's “Religion and the Founding of the American Republic, Religion in Eighteenth-Century America”

Congregations Split

Christine Leigh Heyrman, a history professor at the University of Delaware, provides an online synopsis of the Great Awakening and its impact. Excerpts:

“Not all looked on with approval. Throughout the colonies, conservative and moderate clergymen questioned the emotionalism of evangelicals and charged that disorder and discord attended the revivals. They took great exception to ‘itinerants,’ ministers who, like Whitefield, traveled from one community to another, preaching and all too often criticizing the local clergy.

“So the first Great Awakening left colonials sharply polarized along religious lines. Anglicans and Quakers gained new members among those who disapproved of the revival's excesses, while the Baptists (and, in the 1770s, the Methodists) made even more handsome gains from the ranks of radical evangelical converts. The largest single group of churchgoing Americans remained within the Congregationalist and Presbyterian denominations, but they divided internally between advocates and opponents of the Awakening, known respectively as ‘New Lights’ and ‘Old Lights.’"

Challenges to traditional Protestantism: Revivalism and the enlightenment

An outline of America's cultural and religious development by City

University of New York.