‘Clausal warfare’

Debate about arcane legal concepts reveals Supreme Court justices' philosophy on fundamental rights

By Bruce T. Murray

Author, The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

As a result of the Supreme Court’s decision in McDonald v. Chicago, all states and municipalities may no longer infringe upon “the right of the people to keep and bear arms.” Heretofore, this restriction only applied to the federal government’s ability to regulate gun ownership. In technical terms, the Second Amendment is now “incorporated.”

— Fourteenth Amendment, Due Process Clause

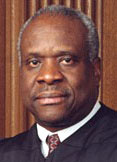

How the Court majority arrived at this conclusion differed, although the result is the same. While four of the justices agreed (or “acquiesced”) that the Second Amendment is incorporated under the “due process” clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Justice Clarence Thomas said it should be incorporated under the “privileges or immunities” clause. In his dissent, Justice John Paul Stevens said the Second Amendment is not incorporated based on what he calls the “liberty clause” (or the due process clause with a different emphasis). The differences among these theories are at once arcane and revealing about the Court’s thinking about fundamental rights.

Justice Sam Alito, writing for the Court, laid out how the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms is incorporated under the concept of “due process.” The test for a due process right inquires whether that right is so “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” that the right can be considered an element of “ordered liberty” – a set of rights that are indispensable to a “civilized” legal system, whether those rights are codified or not.

“Due process protects those rights that are the very essence of a scheme of ordered liberty and essential to a fair and enlightened system of justice,” Alito wrote, citing the 1937 case, Palko v. Connecticut.

Alito then narrows the scope of ordered liberty: He’s not looking for just “any” scheme of ordered liberty, but “our” version of it. He notes that the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Japan, and most European countries either ban or severely limit handgun ownership. Since all of these countries have democratic systems and values similar to the United States, there must be something particular about the American system of ordered liberty as it relates to gun ownership, Alito reasoned.

In a series of decisions in the 1960s, “the Court made it clear that the governing standard is not whether ‘any civilized system [can] be imagined that would not accord the particular protection.’ Instead, the Court inquired whether a particular Bill of Rights guarantee is fundamental to our scheme of ordered liberty and system of justice,” Alito wrote. “Under our precedents, if a Bill of Rights guarantee is fundamental from an American perspective, then, unless stare decisis counsels otherwise, that guarantee is fully binding on the States and thus limits (but by no means eliminates) their ability to devise solutions to social problems that suit local needs and values.”

— Fourteenth Amendment, Privileges or Immunities Clause

Justice Thomas, while agreeing with the majority’s characterization of the right to bear arms as a fundamental right, wrote a separate opinion stating that the Second Amendment would be more appropriately incorporated through the “Privileges or Immunities” clause of the Fourteenth Amendment rather than through the Due Process Clause. The arcane distinction is again revealing about the justice’s philosophy on fundamental rights.

“I cannot agree that the Second Amendment is enforceable against the States through a clause that speaks only to ‘process,’” Thomas wrote. “The notion that a constitutional provision that guarantees only ‘process’ before a person is deprived of life, liberty, or property could define the substance of those rights strains credulity for even the most casual user of words.”

In an “originalist” or “textualist” vein, Thomas said the Court, rather than attempting to define broad concepts such as ordered liberty – and determining which liberties are “fundamental” or not – the Court should instead look to the content of the Fourth Amendment and consider the intent of its framers.

“I believe the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment offers a superior alternative, and that a return to that meaning would allow this Court to enforce the rights the Fourteenth Amendment is designed to protect with greater clarity and predictability than the substantive due process framework has so far managed,” Thomas wrote.

In support of his position, Thomas explores the history and debates surrounding the drafting of the Second and Fourteenth Amendments. His lengthy examination covers the Founding period, the post-Civil War period and later eras.

“This history confirms what the text of the Privileges or Immunities Clause most naturally suggests: Consistent with its command that ‘no State shall abridge’ the rights of United States citizens, the Clause establishes a minimum baseline of federal rights, and the constitutional right to keep and bear arms plainly was among them,” Thomas wrote. “In my view, the record makes plain that the Framers of the Privileges or Immunities Clause and the ratifying-era public understood – just as the Framers of the Second Amendment did – that the right to keep and bear arms was essential to the preservation of liberty. The record makes equally plain that they deemed this right necessary to include in the minimum baseline of federal rights that the Privileges or Immunities Clause established in the wake of the War over slavery.”

Defining liberty

In his dissent, Justice John Paul Stevens explained how, according to Court precedent, “process” and substance are woven together in the due process clause – which he alternatively calls the “liberty clause.”

— Fourteenth Amendment, Liberty and Due Process Clauses

“The first, and most basic, principle established by our cases is that the rights protected by the Due Process Clause are not merely procedural in nature. At first glance, this proposition might seem surprising, given that the Clause refers to ‘process.’ But substance and procedure are often deeply entwined,” Stevens wrote. How so? First, the justice said to look at the text of the clause: Only three words away from the words “due process” is the word “liberty” – which, according to Stevens, is the key word of the clause. “Upon closer inspection, the text can be read to impose nothing less than an obligation to give substantive content to the words ‘liberty’ and ‘due process of law,’” he wrote. “As I have observed on numerous occasions, most of the significant 20th-century cases raising Bill of Rights issues have, in the final analysis, actually interpreted the word ‘liberty’ in the Fourteenth Amendment.”

So how does the Court define such a broad and “majestic” word as liberty, and apply it to the case presented? Stevens looks to precedent, “reasoned judgment”; and never to “subjective, personal and private notions.”

“We have eschewed attempts to provide any all-purpose, top-down, totalizing theory of ‘liberty.’ That project is bound to end in failure or worse,” he wrote. But “significant guideposts do exist” as to what constitutes a trespass against liberty – among them, “government action that shocks the conscience, pointlessly infringes settled expectations, trespasses into sensitive private realms or life choices without adequate justification, perpetrates gross injustice, or simply lacks a rational basis will always be vulnerable to judicial invalidation. Nor does the fact that an asserted right falls within one of these categories end the inquiry. More fundamental rights may receive more robust judicial protection, but the strength of the individual’s liberty interests and the State’s regulatory interests must always be assessed and compared. No right is absolute,” Stevens wrote.

“We have eschewed attempts to provide any all-purpose, top-down, totalizing theory of ‘liberty.’ That project is bound to end in failure or worse,” he wrote. But “significant guideposts do exist” as to what constitutes a trespass against liberty – among them, “government action that shocks the conscience, pointlessly infringes settled expectations, trespasses into sensitive private realms or life choices without adequate justification, perpetrates gross injustice, or simply lacks a rational basis will always be vulnerable to judicial invalidation. Nor does the fact that an asserted right falls within one of these categories end the inquiry. More fundamental rights may receive more robust judicial protection, but the strength of the individual’s liberty interests and the State’s regulatory interests must always be assessed and compared. No right is absolute,” Stevens wrote.

History is an important factor in assessing terms such as liberty, due process and privileges or immunities, but it is not nearly as conclusive as the “originalists” on the Court claim it to be; nor does the Court majority’s historical analysis amount to good legal reasoning or good law, according to Stevens.

“A rigid historical methodology is unfaithful to the Constitution’s command. For if it were really the case that the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of liberty embraces only those rights so rooted in our history, tradition, and practice as to require special protection, then the guarantee would serve little function, save to ratify those rights that state actors have already been according the most extensive protection. That approach ... promises an objectivity it cannot deliver and masks the value judgments that pervade any analysis of what customs, defined in what manner, are sufficiently rooted; it countenances the most revolting injustices in the name of continuity, for we must never forget that not only slavery but also the subjugation of women and other rank forms of discrimination are part of our history; and it effaces this Court’s distinctive role in saying what the law is, leaving the development and safekeeping of liberty to majoritarian political processes. It is judicial abdication in the guise of judicial modesty,” Stevens wrote.

“No, the liberty safeguarded by the Fourteenth Amendment is not merely preservative in nature but rather is a dynamic concept. Its dynamism provides a central means through which the Framers enabled the Constitution to endure for ages to come, a central example of how they wisely spoke in general language and left to succeeding generations the task of applying that language to the unceasingly changing environment in which they would live.”

See Justice Stephen Breyer's dissent here.

More analysis of McDonald v. Chicago

Part I: From gun rights to religious liberty

Legal theories in recent First and Second Amendment cases shed light on ‘judicial activism’ vs. restraint

Part II: ‘Clausal warfare’

Debate about arcane legal concepts reveals justices' philosophy on fundamental rights

Part III: Originalism and African-American history

For justices who follow ‘originalist’ thinking, history reveals the law

Further reading

Should privileges or immunities be free?

“I believe that the content of such citizenship must be more than just a set of privileges conferred by birth or naturalization.” — Eric Liu, former speechwriter and advisor to President Bill Clinton