Faith-based initiatives:

Following a new course of social service in America

By Bruce T. Murray

Author, Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

A new course

– Ram A. Cnaan

President George W. Bush’s Faith-Based and Community Initiative marked a significant new course in national policy toward social welfare. Along with the Charitable Choice legislation passed in 1996, the significance of the Faith-Based Initiative is rivaled most recently by the Great Society program and the War on Poverty in the 1960s.

“The United States has embarked on a new welfare experiment that utilizes faith-based providers as equal partners,” said Ram A. Cnaan, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Social Work.

Somewhat surprisingly, President Obama, rather than discontinuing the program, re-launched it early in his presidency as the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships. Obama’s program is more low-key than his predecessor’s, but the concept is the same.

By whatever name, faith-based initiatives raise many issues of debate, central among them the First Amendment and the doctrine of separation of church and state. It has also raised an awareness of the nation’s religious strength and character – something President Bush talked about frequently. The driving force behind faith-based initiatives is the nation’s spirit of charity and compassion – or so the political rhetoric goes. But in this case, the rhetoric matches reality, Cnaan said.

“The United States has the highest rate of volunteerism in the world, and the U.S. has the largest amount of people spending the largest amount of hours to causes of their heart,” he said.

In addition, Cnaan said people who are involved in religious congregations are more likely to volunteer their time to non-church activities.

Charitable Choice

Bush’s Faith-Based Initiative – and the subsequent Obama version – expand on the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, also known as “Charitable Choice.” The law was designed to encourage increased involvement of religious-based organizations in delivering social services.

Charitable Choice, introduced by then-Senator John Ashcroft and embraced by the Clinton administration, opened the door for faith-based organizations (FBOs) and congregations to receive public funding for programs while preserving their religious nature.

In 1998, the scope of Charitable Choice was expanded to include Community Block services; and in 2000, it was further extended to include drug treatment programs.

Charitable Choice has several controversial provisions, among them:

- It exempts faith-based providers from compliance with employment

polices mandated by section 702 of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The exemption

allows faith-based organizations to hire from within, so

FBO's may hire based on religious commitment rather than merit or experience.

- It allows providers the right to refuse

clients, such as unadherants, gays and lesbians, and people of other

faiths.

- Charitable Choice has been challenged for violating the First Amendment by providing public funds to be used indirectly to enhance religious goals, such as Bible study, prayer and other religious activities.

Before Charitable Choice, faith-based organizations and congregations providing government-supported social services had to remove all religious symbols from the service location and forgo required religious ceremonies such as prayers before meals.

President Bush’s Faith-Based and Community Initiative expanded upon Charitable Choice by further encouraging faith-based organizations in providing social services. Bush also ordered the creation of a Faith-Based Initiative office within seven federal executive agencies — the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Department of Labor, the Department of Justice, the Department of Education, the Department of Agriculture, and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Executive decision

– George W. Bush

Bush’s Faith-Based Initiative was controversial, among other reasons, in that it was advanced entirely at the president’s discretion, without additional legislation beyond the Clinton-era Charitable Choice. Bush had initially had sought congressional approval. In 2001, the House passed a bill that followed closely the administration’s proposal, but the Senate balked. Subsequent attempts to get legislation passed failed. Undaunted, President Bush proceeded with the Faith-Based Initiative using his executive powers.

“I got a little frustrated in Washington because I couldn’t get the bill passed out of the Congress,” Bush said at the 2004 Faith-Based and Community Initiatives Conference in Los Angeles. “They were arguing process. I kept saying, wait a minute, there are entrepreneurs all over our country who are making a huge difference in somebody’s life; they’re helping us meet a social objective. Congress wouldn’t act, so I signed an executive order – that means I did it on my own.”

Many observers in Congress and elsewhere aren’t so sure this is a good way for government to do its business, but the president proceeded throughout his administration with little in the way of “checks or balances” to stop his program. Although faith-based initiatives have been challenged many times in the courts, with various outcomes, the lawsuits ultimately were unsuccessful in halting Bush’s program.

“The Bush Administration has made concerted use of its executive powers and has moved aggressively through new regulation, funding, political appointees and active public outreach efforts to expand the federal government’s partnerships with faith-based social service providers in ways that don’t require Congressional approval,” according to a 2004 report by Anne Farris, Richard P. Nathan and David J. Wright, written for the Roundtable on Religion and Social Welfare Policy.

(Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective includes an in-depth analysis of the legal issues involved with faith-based initiatives.)

History of faith-based social services

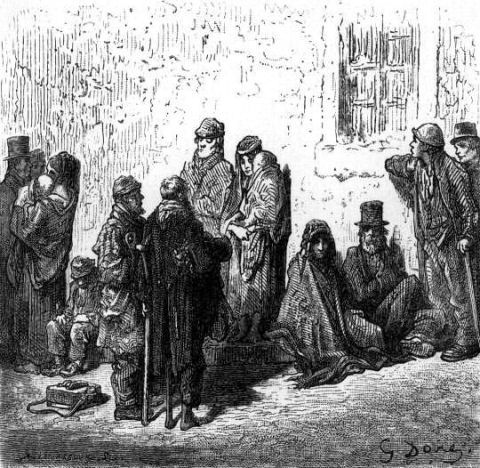

Collaboration between government and faith-based groups in delivering social services did not begin with George W. Bush’s Faith-Based Initiative. It is part of a long process that has evolved significantly since America’s beginnings. In early Colonial times, churches in England and America were less involved in social welfare; they were more embroiled in squabbles over doctrine, conflict with the Catholic Church and the ongoing Protestant Reformation.

Collaboration between government and faith-based groups in delivering social services did not begin with George W. Bush’s Faith-Based Initiative. It is part of a long process that has evolved significantly since America’s beginnings. In early Colonial times, churches in England and America were less involved in social welfare; they were more embroiled in squabbles over doctrine, conflict with the Catholic Church and the ongoing Protestant Reformation.

In Elizabethan England, the Poor Laws were enacted in 1601 to provide relief for the indigent. The Poor Laws were the law of the land in both England and the colonies. In their time, the Elizabethan Poor Laws were the most revolutionary program for assisting the indigent, according to Cnaan.

It was not until the 1880s that religious organizations in America began to get involved in social services in a systematic manner.

“In the United States we take it for granted that social services are provided by religious groups, but it wasn’t always that way,” Cnaan said.

In Europe, the central governments are the provider of social services, and church-state conflicts are not an issue. Also, in Europe's social democracies, there is a broad consensus that government should use taxpayer money to provide social services. Advocating social welfare programs in Europe does not entail the risk of being accused of being a “socialist.”

“The issue of government using public money to support faith-based social services does not exist elsewhere in the world,” Cnaan said.

(Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective includes a detailed history of faith-based initiatives.)

Faith-based motivation

Bush’s Faith-Based Initiative was predicated on the president’s own personal faith as well as the strength of religious congregations in the United States.

A survey by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, “Religion in American Life”, indicates that religion plays an important role for the majority of Americans.

According to the study,

- 64 percent said religion is a very important in their lives.

- Nine in 10 pray at least weekly.

- Six in 10 attend religious services monthly.

Another Pew study, “Among Wealthy Nations, U.S. Stands Alone in its Embrace of Religion,” indicates that Americans remain overwhelmingly religious in an otherwise secular Western world. In the most religious European nation, Great Britain, only 33 percent said religion plays a very important part in their lives. In France, the figure was only 11 percent.

“America is a very religious country,” said Cnaan, a native of Israel. “One of the things that struck me is how little this is discussed and how little it is acknowledged.”

Cnaan said the United States has bucked the secularization theory that as nations modernize and industrialize they will give up religion.

“It was once predicted that as technology, education and knowledge of the world increased, religion would decrease. In other words, it was assumed that religion would serve people when they don’t understand the world around them; and people with rational abilities and the power to control technology would find religion obsolete. In Europe this hypothesis is supported; in Europe, in every generation there is a decrease in religiosity; but in the United States, this theory is totally rejected,” he said.

Trends indicate continuity in this regard. Cnaan and his colleagues conducted a national survey of young people, ages 11-18, and found religious participation high. Among their findings:

- 84 percent reported religion to be important in their lives.

- 67 percent attend a place of worship at least monthly.

- 41 percent are members of a religious-based youth group.

“This means the upcoming generation will be as religious as the previous generation,” Cnaan said. “These findings are supported by three other national studies.”

Religious diversity

– Ram A. Cnaan

The United States is the most religiously diverse nation in the world. Although collectively Protestants are still the largest religious group, no single denomination of any kind forms a majority. The largest single religious group are Catholics, followed by Southern Baptists.

“We have no group that can claim the country is theirs. Every religious group is a minority,” Cnaan said.

In Europe, despite the religious apathy, every country has a majority religion, by 80-90 percent, following the traditional established religion of each nation.

Disestablishment in America eliminated the individual established churches in the various states. Disestablishment also dramatically changed the way religion was “delivered.”

“Finally we have a clergy that brings the word of God but is not sure about the next paycheck. Suddenly, we have a clergy that has to be meaningful to people they work for who voluntarily pay to support congregation,” Cnaan said.

The Pew study on religion also found that 36 percent in congregants attend a place different than their parents, in contrast to only 1 in 100 in the rest of the world.

“This is a society of seekers,” Cnaan said.

The appeal of congregations

– Ram A. Cnaan

In focus groups Cnaan held on religion in Philadelphia, the number one issue was children and values.

“When I ask people why they join a congregation, they all say this is the only place where values are being taught and moral instruction is being provided,” he said. “Public schools don’t provide students moral instruction. Parents say, ‘I want someone else – not just us – to tell them there’s right and wrong.’”

People also congregate to form social bonds and networks. It is not surprising, then, that congregations are highly segregated along racial, ethnic and class lines.

“People congregate with people like themselves – not only ethnically but social class background,” Cnaan said. “Segregation gives the sense of knowing people you know and trust; so when you enter a place of worship and become a member, you also enter a social network and gain support and willingness to do for others because you are doing for people you trust.”

Why do congregations provide social services?

“The overwhelming majority don’t do it to covert people,” Cnaan said. “They want to actualize faith - it’s faith in action. It strengthens the community inward rather than bringing people from outside. It’s an excellent mechanism to solidify the membership. It’s doing well among friends and colleagues, and that makes you feel good. People get great gratification.”

The Philadelphia project

– Ram A. Cnaan

Cnaan and Stephanie Boddie of the University of Pennsylvania led a study of congregations in Philadelphia that shows high participation of the population in church activities and volunteer social services.

The study identified 2,095 congregations and received survey results from 1,376 of them. Of those surveyed, 88 percent provide at least one social program. On average, each congregation provides 2.4 programs and serves 102 people per month.

The replacement value of these services – how much it would cost to pay others to provide the same services – is estimated at $247 million.

The most frequent programs provided by congregations include food pantries, summer day camps and recreational programs for youth. Congregations also routinely provide free space for voting stations, 12-step programs, scouts, and day care centers. More than half of clergy members refer congregants to health, vocational, legal or financial services.

Other findings from the survey include:

- About 47 percent of the Philadelphia population belongs

to a congregation. Congregation size ranges from six to 13,000, with

an average of 346 members, including children.

- 13 percent of the congregations surveyed conduct joint

worship or prayer services with other religious groups and collaborate

in providing other social services.

- The congregation-sponsored programs serve an average

of 39 members of the congregation as well as 63 nonmembers.

- 38 percent of the congregations reported financial

difficulties; 52 were getting by, and only 10 percent reported no financial

problems.

- About half of the clergy surveyed graduated from a

theological seminary. One quarter of the congregations have no full-time

clergy.

- On average, a congregation in Philadelphia has been at its present location for 50 years.

Another study of West Philadelphia found 433 places of worship in an area of six square miles, which translates to an average of 33.3 congregations per square mile.

The longest distance between two congregations is .8 miles, including divisions by parks. If weren’t for the parks, the distance would be .4 miles.

“There is no other social organization that is so widespread in the community as congregations,” Cnaan said.

Conclusions

– Ram A. Cnaan

Despite the importance of religious congregations in America, Cnaan believes faith-based organizations are not the panacea for the nation’s social welfare problems.

“I don’t believe congregations can replace the government, yet there is a lot of potential,” he said.

President Bush spoke passionately about volunteerism and the potential of his faith-based initiative. There is a great deal of anecdotal evidence to support the effectiveness of faith-based programs, but little scientific data.

“There is no data to say faith-based organizations are more effective or efficient, but there is no data to say they are less effective,” Cnaan said. “In principle, when you allow more groups to compete – when you open the door for more groups to participate – you increase the chances of quality. Without testing it, we don’t know.”

Cnaan pointed to other contexts in which the government contracts with private organizations for services and material, such as defense.

“Are faith-based services different from subcontracting with for-profit companies like Lockheed-Martin?” he asked. “The issue shouldn’t be whether the organization is faith-based; the issue should be: Can they provide services? If we don’t try, we’ll never know.”