With ‘God on our side?’

Following the contours of civil religion in America

By Bruce T. Murray

Author, Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

Contours of civil religion

The words “civil” and “religion” make an odd pairing when put together – seemingly self-contradictory and oxymoronic, like “jumbo shrimp” or “military intelligence.”

Civil religion, this unlikely pairing of words, is likewise difficult to define; moreover it is not well-known or widely discussed. Yet, civil religion is pervasive and everywhere in American public life – especially in politics. Whenever a political campaign heats up, it is likely that one will hear civil religion from the stump; whenever there is a national emergency, civil religion bubbles up in the rhetoric; and civil religion can even be found in popular culture.

Assisting in its definition, civil religion has many synonyms: It is alternatively called “civic faith,” “public piety,” or “republican religion” (small “r”). Some explain it in terms of a “social contract”; some call it call it a “creed”; while others say there’s no such thing as any of it. Civil religion has many definitions – usually long yet incomplete.

The late public intellectual Rowland A. Sherrill summed up civil religion this way:

“American civil religion is a form of devotion, outlook and commitment that deeply and widely binds the citizens of the nation together with ideas they possess and express about the sacred nature, the sacred ideals, the sacred character, and sacred meanings of their country – it’s blessedness by God, and its special place and role in the world and in human history. Civil religion is the mysterious way that religion, politics, ideas of nationhood, patriotism, etc. – energized by faith outlooks – represents a national force. It gets very little careful thought. But we live in it, and we appeal to it all of the time.”

“American civil religion is a form of devotion, outlook and commitment that deeply and widely binds the citizens of the nation together with ideas they possess and express about the sacred nature, the sacred ideals, the sacred character, and sacred meanings of their country – it’s blessedness by God, and its special place and role in the world and in human history. Civil religion is the mysterious way that religion, politics, ideas of nationhood, patriotism, etc. – energized by faith outlooks – represents a national force. It gets very little careful thought. But we live in it, and we appeal to it all of the time.”

Civil religion is perhaps more easily graspable by example than by description. Some illustrations:

“The same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe – the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hands of God.” — John F. Kennedy in his inaugural address, Jan. 20, 1961

“I’ve spoken of the shining city all my political life, but I don’t know if I ever quite communicated what I saw when I said it. But in my mind it was a tall proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, wind-swept, God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace ...” — Ronald Reagan, Farewell Address to the Nation, Jan. 11, 1989

“It is through the truthful exercising of the best of human qualities – respect for others, honesty about ourselves, faith in our ideals – that we come to life in God’s eyes. It is how our soul, as a nation and as individuals, is revealed.” — Bruce Springsteen, “Chords for Change,” Aug. 5, 2004

The connection between faith and nationhood, and the connection between ideals of place and purpose are all evident in these words and sentiments – which are expressed not only by presidents but also by a rock star; and many more unlikely examples abound.

Civil religion is not mere rhetoric, but a set of deeply held beliefs that are commonly understood by most Americans, even if the exact definition and terminology would elude them. And civil religion is not the sole purview of politicians, but it belongs to anyone who claims it.

Origins of civil religion

In 1630, John Winthrop delivered these words en route to the Massachusetts Bay Colony – where he would be the first governor:

“Thus stands the cause between God and us: We are entered into a covenant with Him for this work; we have taken out a commission. ... For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people upon us. We have professed to enterprise on these actions upon these ends.”

“Thus stands the cause between God and us: We are entered into a covenant with Him for this work; we have taken out a commission. ... For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people upon us. We have professed to enterprise on these actions upon these ends.”

Winthrop’s words form the basis of American civil religion and cover the key themes:

- The idea of “covenant” or “commission” – spoken here in a religious sense but with a practical application for the establishment of a new society. The covenant would eventually become a constitution.

- The imagery of a “city on a hill” – the idea that the American experiment will be an example to the world.

- A pledge to “work” – the embodiment of the so-called “Protestant work ethic,” now simply the “American work ethic.”

Civil religion begins with Winthrop, and has been carried on through the centuries. In his Farewell Address to the Nation, Ronald Reagan readily attributed his “shining city upon a hill” imagery to Winthrop: “What he imagined was important because he was an early Pilgrim, an early freedom man … and like the other Pilgrims, he was looking for a home that would be free.”

Winthrop was a pilgrim from another land, who then became a pilgrim in his own land. Faith and freedom are tied together in a new world – free from the shackles of the Old World, yet with an eye toward an even older Holy Land.

“The people set to come here were thinking about themselves in a biblical language, especially the language of the Hebrew Bible,” Sherrill said. “They referred to this place before they even got here as ‘God’s new Israel’ and ‘God’s new Zion.’”

The Pilgrims and Puritans who founded New England had a symbolic understanding of themselves and their actions, as is readily discernable in Winthrop’s words. Immediately before his “city on a hill” passage, Winthrop states:

“We shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies; when he shall make us a praise and glory that men shall say of succeeding [generations]: ‘The Lord make it likely that of New England.’”

As Sherrill interprets, “These early settlers thought they were people who had been specially picked out to complete the Reformation on these shores; to create a ‘city upon a hill’ that would be a model to the European world. They thought of themselves as the next chapter in Biblical history.”

So, when Americans pledge allegiance to the flag – “one nation, under God” – they are not reciting empty words or following a right-wing conspiracy. When the president concludes every speech with “God bless America,” as vapid and hackneyed as it may seem, there is actually some substance behind it.

“There is a religious aura and coloration in the ways many Americans think about, live within and operate in relation to their ideas of their country as sacred entity,” Sherrill said. “People believe the county has been specially blessed by God, and that means they, the Americans, have been blessed. Their country, and therefore they, have a special place and role in the world and in human history.”

This idea carried through colonial times and helped fuel the American Revolution and beyond. “The success of the Revolution reinforced the idea that the American form of government must be sanctified, and Americans must be special because they emerged victorious,” Sherrill said.

Before the Civil War, biblical language was wrongly used to justify slavery, but later the vocabulary of civil religion was effectively employed to criticize the nation for falling short in its covenant.

“Martin Luther King, Jr. criticized the country in its own religious terms – using the country’s own religious rhetoric to lodge a critique,” Sherrill said.

Civil religion and politics

Civil religious language most frequently shows up in political discourse, on the campaign trail and in political speeches. When Bill Clinton talked about a “New Covenant” he was talking in the terms of civil religion; George W. Bush frequently mixed both religious and civil religious language; and Barack Obama, in his first debate with Sen. John McCain, said that as president, he would “restore that sense that America is that shining beacon on a hill.” Like Reagan, Obama reached right back to Winthrop.

“Using this vocabulary is very effective. It has effect of drawing people in in the way they wish to be drawn in and identified. The vocabulary can be absorbed by people with so many different points of view. Speechwriters know how civil religion works,” Sherrill said.

But civil religion can also be used to pander and manipulate. “So much of it out there goes unacknowledged and unstudied that it can be more dangerous than useful. It can be used to create fraudulent sentiments,” Sherrill said.

Sherrill urged journalists, when they detect a politician using the language of civil religion, to make note and follow up. “It would lift level of political and religious discourse if you would stop and say, ‘Wait just one fine minute, what do you mean by that?’” he said.

Church and state

Civil religion gets sticky and confusing in the church and state debate. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between what is civil religion and what is “God talk,” as C. Welton Gaddy terms it. Gaddy, a pastor and president of the Interfaith Alliance, was particularly critical of George W. Bush’s religio-political language that was evident in so much of Bush’s public speech.

“The president’s merger of political and religious language clearly suggested that the speaker’s way was the right way, indeed, God’s way, and that all who disagreed with him had chosen another path,” Gaddy wrote in his chapter, “God Talk in the Public Square” (Quoting God, Baylor University Press, 2005). “The public’s present infatuation with ‘God bless America’ – whether as a genuine prayer for a righteous nation, as a patriot boast of divine blessing, or as strategic rhetoric employed to build support for a politician’s candidacy for public office or for a national policy – epitomizes the reality, confusion and danger of God talk in the public square. So pervasive is the God-talk phenomenon that it has contributed significantly to the politicization of religion and the ‘religiofication’ of politics in the national public square.”

Nauseating as it may be to many, when the president uses religious language in his speech, it does not constitute a church-state conflict because the president is merely expressing his own views and not promulgating laws “respecting an establishment of religion,” as the First Amendment prohibits.

“Too many people get religion and politics confused with church and state,” Sherrill said. “Religion and church, although related, are not the same thing; politics and state are related, but they’re not the same thing.”

Nonetheless, as Sherrill noted, individual religious belief inevitably informs the political decision making process, thus making absolute separation of church and state impossible.

“As long as people are religious and as long as people are political – and that’s almost unavoidable – religion and politics will get mixed together,” he said. “So every time you get a case in which religion and politics get mixed together, it’s not necessarily a church-state thing.”

For example, it should not be surprising when communities made up largely of evangelical Christians would vote in a referendum to make their county dry; or if voters in a conservative state vote to ban same-sex marriage, or to impose restrictions on abortion.

“And it ought not be the least bit surprising that members of the Roman Catholic community in the United States use the doctrines and teachings of their church to think their way through the political aspects and public policy issues of the abortion debate,” Sherrill said.

‘With God on our side?’

Civil religion is not to be confused with patriotism and its various negative exponents – nationalism, jingoism and chauvinism. Nonetheless, civil religion and patriotism do intersect, as Sherrill describes:

“Civil religion involves the definition of patriotism – the love and commitment to one’s homeland – that is built right into to civil religion. But only when you add on the religious significance and character of the country that warrants such love and commitment does it go from simple patriotism to civil religion. Civil religion also relates to nationalism – a passionate adoration of the state, its governing authority and civil order. Civil religion adds to that the idea that the governing authority and civil order are sanctified in some way with spiritual or religious significance.”

The public response to the Sept. 11 attacks was, at face value, a simple expression of patriotism: waving flags, singing songs and commiserating. But in addition, millions of Americans sought refuge and meaning in churches, impromptu neighborhood prayer meetings and candlelight vigils. The injection of religious worship elevated the response to something more than patriotism and flag-waving.

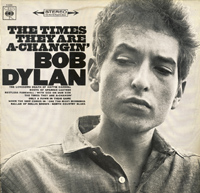

But if taken too far, patriotic sentiments can fall off a cliff and into the black hole of national chauvinism. And with religion mixed in, God becomes a steamroller for nationalistic triumph – what Bob Dylan so poignantly critiqued in his 1964 song, “With God on Our Side”:

“Oh the history books tell it;

“Oh the history books tell it;

They tell it so well:

The cavalries charged;

The Indians fell.

The cavalries charged;

The Indians died.

Oh the country was young,

With God on its side.”

Sociologist Robert Bellah cautions against the nationalistic corruption of civil religion, what he calls “the idolatrous worship of the state”:

“American civil religion is not the worship of the American nation but an understanding of the American experience in the light of ultimate and universal reality. Civil religion at its best is a genuine apprehension of universal and transcendent religious reality as seen in or, one could almost say, as revealed through the experience of the American people,” Bellah wrote in his 1967 article. “Civil Religion in America.”

Civil religion, diversity and multiculturalism

In modern times, American civil religion finds itself in competition with a new civic ideal, diversity & multiculturalism. Will civil religion be consumed by the new ethos? Or will civil religion incorporate the new ideals to form a new dialectic?

According to Sherrill, pluralism is an inherent element of civil religion, and therefore it incorporates the vast diversity of America. American civil religion transcends ethnic and religious differences.

“Civil religion cuts beyond traditional religious groupings. You could be a Presbyterian, Quaker or Jew and disagree with each other; but in terms of civil religion you all agree on some fundamental things regarding the nature of your country,” he said. “American civil religion provides background, ideas and vocabulary. It is accessible to Americans if they’ve been here since 1620 or arrived from Vietnam six weeks ago. There are certain ways the country talks about itself as the land of opportunity, an open society, a democratic way of life, etc. which has a pull on the imagination of people who are fleeing horrible circumstances elsewhere.”

Nonetheless, there are different versions of civil religion that operate and in different regions of the country and sometimes compete with one another in the diverse & multicultural milieu.

“Civil Religion works at a national level and filters down into local communities; and it is very different on the East Coast, the West Coast and the Southwest,” Sherrill said. “Every group in America that is religious and serious about its national character incorporates civil religion in its own terms. Civil religion in Los Angeles is a huge contest among so many different groups, each of whom has its own version of the religious meaning of the country. They would disagree on almost every issue except for the belief that the America sanctions the smaller version that they enact in their particular neighborhood.”

What’s so special about us?

Most nations have some form of civil religion or a national creed. In Israel, the sense of national mission permeates the society; in France, “Frenchness” is more sublime than anything found in a gothic cathedral; and the Germans have practically made a religion out of frugality – what Max Weber would say is tied right back into the same Protestant values that Winthrop preached. Among nations, the United States has a particular abundance of what makes civil religion, according to Sherrill.

“In America, we don’t just have material wealth, but also a ‘supply side of spiritual wealth.’ It’s there; you just have to tap it,” he said. “We go through periods when civil religion lies dormant, especially during times of economic prosperity; and then when we get something like a war, it flames back up again.”

Although civil religion sometimes changes forms, Sherrill believes it is here to stay. “Civil religion has gone through permutation after permutation throughout the course of our history. Every significant historical event that the country passed through had to get folded into it somehow. There are signs and remnants of religion in places where you don’t expect it. Civil religion is voracious and will gobble up anything it thinks useful,” he said.

In the final analysis, is civil religion good or bad? For Sherrill, it is both:

“The power to compel and to elicit a sense of bondedness to one’s fellow countryperson is the best part of civil religion when it works. Civil religion involves some of the best resources we have as a nation, but it is potentially some of the most destructive stuff because it can be manipulated so easily by cynical people. I believe civil religion, if done with integrity and honesty, does represent the source of common aspirations if you don’t push it too hard and make it too specific.”

Sidebars

Elements of civil religion

Civil religion has the following elements:

- Myths – Sacred stories, parables, and legendary acts of heroism, such as George Washington sailing across the Delaware River on Christmas, the bloody cleansing of the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln’s ascent as the savior of the nation.

- Rituals – Ceremonies and actions that define communities and cross denominational lines such as the honoring of the dead after Sept. 11, monuments to people who died in battle, and the Pledge of Allegiance – with the phrase, “under God.”

- Ethics – Codes of moral conduct, what the Puritans called “cutting covenants with the Lord,” and enacting covenants with one another.

- Aesthetics – Public buildings and courthouses built in the Classical style, and civil religion expressed in art, music and popular culture.

- Doctrines and documents – The Declaration of Independence, the Gettysburg Address and the Bill of Rights.

- Patriotic social groups such as the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Themes of civil religion

- Chosenness – The idea that the nation and its citizens have somehow been chosen by God for a higher purpose.

- Freedom – A universal and a religious value, as Winthrop explained in “Model of Christian Charity.”

- Individualism – “No country in the history of this planet has ever put such an emphasis on individual freedom. But in so doing you also put a certain kind of obligation on individuals in order to be part of the covenant,” Sherrill said.

- The American dream – Rags to riches, or more crassly, making lots of money. “What’s the matter with that?” Sherrill asked, “–only when it doesn’t involve other civil covenants.” Therefore, wealth must somehow be given back to the community in the form of philanthropy or social services.