Finding the common threads of religious liberty

Debate over the role of religion in public life goes back four centuries

By Bruce T. Murray

Author, Religious Liberty in America: The First Amendment in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

Déjà vu

— Charles C. Haynes

If the news pundits and commentators are an accurate gauge, America is polarized – more than anyone can remember. Controversy over moral and religious issues such as abortion, marriage, and the Pledge of Allegiance – “under God” – has pitted Americans against each other to an unprecedented degree, or so it might seem. Based on the tenor of talk shows, Web logs and political strategists, it would appear America is moving into dangerous uncharted territory in its national discussion.

But these debates are really nothing new. Four centuries ago, the early Americans were arguing over the same underlying issues: What is the place of religion in society? To what degree do we separate church from state? How does society tolerate people of different faiths – or no faith at all?

“It all boils down to the basic question, ‘What kind of nation are we, and what kind of nation are we going to be?’” said Charles C. Haynes, senior scholar at the First Amendment Center. “In the 1600s, the argument was even less friendly than today.”

The debate between John Winthrop (1587–1649), the first governor of Massachusetts, and Roger Williams, (1613–1684) a founder of Rhode Island, embodies the early clash of philosophy between church and the embryonic American state. Winthrop and Williams were both Puritan, a form of Christianity derived from the teachings of church reformer John Calvin. While Winthrop sought to keep his Puritan colony tightly knit together and free of dissent, Williams advocated freedom of conscience and complete free exercise of religion.

Winthrop and Williams emerge as archetypes in the ongoing debate in America regarding religion in public life. In the 17th century, the terms of the debate and the posturing of opposing camps were much the same as they are today. In modern terminology, Winthrop would represent the conservative side, and Williams the liberal, “progressive” or even radical view. Both men were deeply committed to their Christian faith, but their interpretations of the Bible led them to very different conclusions.

“These were two very different visions of what kind of society could be built in this place,” Haynes said. “If you go back in history, you can see how the same debate has echoed throughout the centuries.”

Winthrop and Williams, despite their philosophical differences and occasional exasperation with one another, maintained friendship and civility – in contrast to today’s modern shout–casts. “It was an argument between friends, and Winthrop and Williams remained friends throughout their entire lives. But their visions were very different,” Haynes said.

City on a hill

In the spring of 1630, with a royal charter in hand, Winthrop led a fleet of 11 vessels and 700 hundred passengers from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Sailing on board the Arabella, Winthrop delivered his landmark sermon, “A Model of Christian Charity,” in which he spelled out the mission he and his followers were about to embark upon:

“Thus stands the cause between God and us: We are entered into a

covenant with Him for this work; we have taken out a commission. ...

For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes

of all people upon us. We have professed to enterprise on these actions

upon these ends.”

“Thus stands the cause between God and us: We are entered into a

covenant with Him for this work; we have taken out a commission. ...

For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes

of all people upon us. We have professed to enterprise on these actions

upon these ends.”

Winthrop’s language echoes the New and Old Testaments – especially Deuteronomy and Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. Many of his followers saw Winthrop as a modern–day Moses, leading his people into the new promised land, the “new Israel.”

“John Winthrop was giving his fellow Puritans a vision of their mission: ‘We are a special nation; we are an example to the world,’” Haynes said. “They thought of themselves as chosen agents of God, modeling themselves on the Hebrews, and entering into a covenant with God. It’s a partnership with God, and God is investing in the community.”

Winthrop’s sermon continues:

“If the Lord shall please to hear us and bring us in peace to the place we desire, then He hath ratified this covenant and sealed our commission, and will expect a strict performance of the articles contained it. But if we shall neglect the observation of these articles which are the ends we have propounded ... the Lord will surely break out in wrath against us.”

Winthrop’s language reflects the Puritans’ particular interpretation of Calvinist philosophy – that God has chosen an “elect” group of people to receive His grace. God’s selection is determined by God alone and not by one’s deeds, petitions or by performing particular rituals. Rather, one’s deeds were taken as evidence of whether or not one was a “visible saint” – a member of the chosen elect. Godly deeds were taken as a good indication of one’s standing with God. But one could never know with complete certainty whether or not one was “chosen,” which led to a certain anxiety, Haynes said.

“This is the heart of the Puritan paradox: If you are a Calvinist and believe the elect have already been determined, then why should you be worried? Calvinist liberation is the idea that there is nothing you can do for your salvation — that is solely in the hands of God. But Calvinist anxiety is, if you don’t appear to be saved, then you probably aren’t,” Haynes said.

“Winthrop’s words tap into the Puritan anxiety: If you live up to what God requires, you will be blessed. If you fail to live up to it, you will be cursed. If you are chosen for this special mission, then you have an obligation to live up to what God requires.”

In his sermon, Winthrop goes on to define his vision of community and man’s obligation to one another:

“Every man might have need of others, and from hence they might be all knit more nearly together in the bond of brotherly affection ... always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, our community as members of the same body.”

Here, the covenant is a collective one: For a good Puritan to live up to his covenant, he must be concerned with the welfare of the community and how others are living up to the covenant. “What one person does affects what others in the community doing; otherwise stated, ‘You will be punished for what I am doing,’” Haynes said.

“This philosophy translates into the moral underpinnings in the nation’s laws; it has shaped our concern for education and our sense of purpose; it has shaped our priorities and what we do in the world and how we are connected to one another. Much of theology has gone out of it, but not the ideas and the philosophy,” he said.

City on a hill in dissent

— Charles C. Haynes

Dissent came to the Massachusetts Bay colony, and it didn’t take long to arrive. In 1631, Roger Williams set sail from England to Massachusetts in search of new spiritual soil. He took his first job as “teacher,” or assistant minister at the First Church in Boston.

“He astonished them almost at once by calling them a false church,” wrote historian Martin E. Marty in his book, Pilgrims in Their Own Land. (Penguin Books, 1984) “True Puritans, he insisted, must separate from the whorish Church of England; yet Bostonians clung to it, hoping to reform it from a distance.”

Although the Protestant Reformation had freed England and northern Europe from the Catholic Church, it did not break the bond between church and state. Established state churches – whether Protestant or Catholic – were still the order of the day.

Roger Williams preached among Native Americans.

Roger Williams preached among Native Americans.Williams was a radical separatist; he believed the true church must separate from what he regarded as the irreformably corrupt Church of England. Winthrop, on the other hand, hoped to purify the Anglican Church, but he did not want to create a confrontation with the crown. But for Williams, the Reformation was incomplete and Christianity was tainted so long as the state was involved.

“Williams believed any society founded on a state religion is corrupt: The state corrupts religion, and then religion corrupts the state. And a state that denies freedom of conscience is corrupt,” Haynes said. “Williams believed you cannot be a true Christian unless it is an act of conscience.”

Williams was searching for the true church he believed was lost all the way back in the year 313, when the Roman Emperor Constantine bestowed imperial favor on Christianity, creating a “Christian Empire” and setting the blueprint for 1,000 years of medieval Christian Europe. Church and state were “inseparate.”

Williams was searching for the true church he believed was lost all the way back in the year 313, when the Roman Emperor Constantine bestowed imperial favor on Christianity, creating a “Christian Empire” and setting the blueprint for 1,000 years of medieval Christian Europe. Church and state were “inseparate.”

“For Williams, the worst word in the English language was ‘Christendom.’ When Christianity becomes Christendom, it is no longer Christianity; it is a corruption,” Haynes said. “When people are Christian because the state is Christian – and it is to one’s advantage to be a Christian – then they are hypocrites. Or, when people refuse to become Christians, the result is ‘rivers of blood.’”

Williams made his case for the cause of conscience dramatically in his 1643 publication, “Queries of Highest Consideration”:

“Oh! since the commonweal cannot without a spiritual rape force the consciences of all to one worship; oh, that it may never commit that rape in forcing the consciences of all men to one worship which a stronger arm and sword may soon (as formerly) arise to alter.”

Williams developed these ideas further in his landmark 1644 treatise, “The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution,” in which he makes the following proclamations:

- “First, that the blood of so many hundred thousand souls of Protestants and Papists, split in the wars of present and former ages, for their respective consciences, is not required nor accepted by Jesus Christ the Prince of Peace.

- “The doctrine of persecution for cause of conscience is proved guilty of all the blood of the souls crying for vengeance under the altar.

- “All civil states with their officers of justice in their respective constitutions and administrations are proved essentially civil, and therefore not judges, governors, or defenders of the spiritual or Christian state and worship.

- “God requireth not a uniformity of religion to be enacted and enforced in any civil state; which enforced uniformity (sooner or later) is the greatest occasion of civil war, ravishing of conscience, persecution of Christ Jesus in his servants, and of the hypocrisy and destruction of millions of souls.

- “It is the will and command of God (since the coming of his Son, the Lord Jesus), that permission of the most paganish, Jewish, Turkish or anti–Christian consciences and worships, be granted to all men ...“

Williams’ detractors, particularly John Cotton of the Boston church, argued that the state must protect itself from heretical practices, Papists and evil in general. Cotton wrote an answer to the “Bloudy Tenent” called “The Bloody Tenent, Washed, And Made White in the Blood of the Lambe,” to which Williams responded with yet another treatise with an even longer title. Even Williams’ friends, like Winthrop, could not fathom the type of religious freedom Williams advocated.

“People thought Williams had to be out of his mind,” Haynes said. “The form of liberty he advocated was dangerous. Surely the state has the right to defend itself against evil.”

Williams believed the community, as a matter or priority, had to protect the individual conscience. His argument for freedom of conscience was grounded in a theological proposition:

“Williams believed God created every human being with liberty of conscience,” Haynes said. “God created human beings with the capacity to turn toward God or turn away. Society or government may not interfere with what God has done. People in any society have the right to be wrong. If they chose to turn away from God, that is between them and God. Williams had a supreme confidence that ‘God can take care of God.’”

This opinion stood in sharp contrast with the general view of the day, which was more concerned with uniformity, according to Winthrop’s vision of a community “knit together.” Williams, on the other hand, argued for complete free exercise of religion – even for Quakers, Catholics and Jews – a revolutionary idea at the time.

“Free exercise means state does not have control of religion, and no one else had imagined a state could exist with that,” Haynes said. “People thought free exercise meant chaos.”

Free exercise is to be distinguished from its lesser cousin, toleration, which could always be withdrawn at the whim of a particular regime. “Williams believed that in the hands of government, toleration is a ‘weasel word,’” Haynes said. “Toleration means that government can allow something one day and then disallow it the next. Toleration means the state still has control over what is Christian and what is not, and it can stamp out what is not in its purview. In terms of personal virtue, Williams might say toleration is good; but in the hands of government, it is dangerous.”

But Williams was also a man of his time. He thought the Catholic Church was evil, and that the Quakers were wrong. He argued with the Quakers vigorously throughout his life.

“He thought everyone should understand the Gospel the way he understood it,” Haynes said. “He was not the founder of ACLU, and he had no love for all different groups. He debated the Quakers to the end and tried to convince them that they were wrong and he was right. The fact that Williams urged tolerance of groups he opposed made his argument for religious liberty even sharper.”

Embryo of the First Amendment

— Isaac Backus

In tracing the birth of the First Amendment, the most logical place to start is with Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and the other Founders. But the basis of religious liberty in America goes back much further, and it begins in these early debates.

The core idea behind the First Amendment – that the government should never interfere with an individual’s freedom of conscience – comes from Roger Williams.

“He was the first to use the term, ‘separation of church and state,’” Haynes said. “The First Amendment – specifically the first 16 words – takes us all the way back to Williams. Williams wanted people to go to church on their own free will, and not be coerced. This is where we get ‘free exercise thereof.’ Williams argued that you can’t have free exercise if you have an established church. He believed we must build a ‘hedge of separation between the garden of the Church and the wilderness of the world.’ Otherwise there would be no chance of having the garden if the state is involved.”

Williams spent most of his life searching for pure Christianity and the “true church.” He became a Baptist, but later withdrew from any congregation and became a kind of sect unto himself, or a “seeker” of his day.

By the time the first Congress convened to pass the Bill of Rights in 1791, Roger Williams was a faded memory from colonial history, and he did not emerge as a popular character for name–dropping among the Founders.

Williams’ role in shaping what was to become the First Amendment was important but indirect – primarily through his influence on political philosopher John Locke, who was influential among the Founders; and Isaac Backus, an important spokesman for religious freedom during the Revolutionary era and the founding period.

Backus, a Baptist minister from Massachusetts, argued for separation of church and state and against taxation for the support of the established church of Massachusetts, the Congregational Church that had been handed down from the Puritans.

“God alone is Lord of the conscience, and hath left it free from the doctrines and commandments of men,” Backus wrote in An Appeal to the Public for Religious Liberty Against the Oppression of the Present Day (1773). “The requiring of an implicit faith, and an absolute blind obedience, is to destroy liberty of conscience – and reason also.”

Like Williams more than a century earlier, Backus used a basic theological argument: Interference with the human conscience is an offense against God, and attempts at such interference represent the worst kind of oppression. A similar argument cropped up later in the landmark Virginia Statue of Religious Freedom (1786), which begins,

“Whereas Almighty God hath created the mind free; that all attempts to influence it by temporal punishments or burdens, or by civil incapacitations, tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness, and are a departure from the plan of the Holy Author of our religion, who being Lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate it by coercions on either.”

The author of the statute was Thomas Jefferson – not one for making theological

arguments, but his core plea is for the cause of conscience, just as Williams

had pleaded more than a century earlier. James

Madison, who steered Jefferson’s bill to passage in the Virginia Assembly,

took the ball and ran with it when the time came to draft the U.S.

Constitution and the First Amendment – of which Madison was a principal

author.

The author of the statute was Thomas Jefferson – not one for making theological

arguments, but his core plea is for the cause of conscience, just as Williams

had pleaded more than a century earlier. James

Madison, who steered Jefferson’s bill to passage in the Virginia Assembly,

took the ball and ran with it when the time came to draft the U.S.

Constitution and the First Amendment – of which Madison was a principal

author.

The genealogy of the ideas Jefferson and Madison permanently imprinted

on the United States goes back to early colonial America, the radical

wing of the Protestant Reformation, and the dissenting Puritans – of whom

Williams is the primary – and perhaps still the most radical spokesman.

The genealogy of the ideas Jefferson and Madison permanently imprinted

on the United States goes back to early colonial America, the radical

wing of the Protestant Reformation, and the dissenting Puritans – of whom

Williams is the primary – and perhaps still the most radical spokesman.

“Roger Williams believed the same Reformed Protestant doctrines his principal opponents believed. But he applied them with a boldness and moral imagination quite beyond the point to which his fellow Puritans were willing to go, and with practical results for political life,” wrote historian William Lee Miller in his book, The First Liberty: Religion and the American Republic (Paragon House Publishers, 1985).

The legacy of Winthrop’s covenant

— Charles Haynes

Williams’ stubborn dissents and pointed arguments carried the essential pollen for what would later develop into the fruits of the First Amendment a century and a half after his time. But it is Winthrop’s vision of a “city on a hill,” as expressed in his “Model of Christian Charity,” that remains the dominant ideal in America.

“You see these ideas throughout American history and still today,” Haynes said. “If there is any one document that echoes out throughout our history to present time, it is this one.”

Winthrop is a favorite for politicians to quote. Ronald Reagan built his presidential career around the image of the “city on a hill.” Presidents who don’t give a “city on a hill” speech are said to be lacking “the vision thing.” George H.W. Bush wasn’t able to capture Reagan’s aura. Bill Clinton talked about a “new covenant,” but didn’t get far with it. George W. Bush dusted off “Providence,” which he often invoked in his formal speeches, including his 2005 State of the Union Address. And Barack Obama, in his first debate with Sen. John McCain, said that as president, he would “restore that sense that America is that shining beacon on a hill.”

“You could take any election cycle, and things from Winthrop’s sermon will be there,” Haynes said. “I don’t think you can be elected president of the United States without some kind of ‘city on a hill’ speech. It resonates with Americans.”

Each political party claims Winthrop, but each party emphasizes different aspects of his philosophy. Republicans emphasize the “city on a hill,” while Democrats emphasize the notion of community “knit together.”

Missing from Winthrop’s speech are words such as “diversity” and “multiculturalism” – so dominant in today’s political dialogue, but not part of the Puritan reality.

“They [the Puritans] were after religious freedom for themselves, but not for other people,” Haynes said. “Conformity was built into their society because much of what they envisioned depended on people having a shared understanding of what their society was going to be about.”

Politicians who invoke Winthrop today conveniently omit the lines immediately following his city on a hill clause:

“If we shall deal falsely with our God ... We shall shame the faces of many of God’s worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going.”

Only the “shining city” side of divine Providence is trumpted on the political stump. But without a complete understanding of Winthrop’s meaning, and without Williams’ view to balance, the “shining” vision can easily degenerate into arrogance, self–aggrandizement, and the chauvinistic notion of “God on our side.”

According to Williams’ interpretation of the Bible, neither New England nor any other colony or country could ever be God’s approximation of a “New Israel”; nor could the people of any country claim to be a special nation of “God’s chosen people.” But since being special and “chosen” is far more politically attractive than the alternative, the selective Winthrop vision has won out.

Witch trials, civil liberties and the Puritan legacy

— Charles C. Haynes

The Puritans are generally not looked upon favorably in history books, popular culture and the media. The Puritans are most commonly known – not for Winthrop or Williams – but for the infamous Salem witch trials, in which about 25 people, mostly women, were executed for allegedly practicing witchcraft.

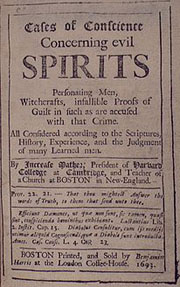

Despite the excesses of the witch

trials, it was the Puritans themselves who put a stop to it. Increase Mather, a Puritan clergyman and president of Harvard College (now Harvard University), played a prominent role in exorcising the witch hysteria.

In his published sermon,

“Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits,”

Mather argued against the use of “spectral evidence” in the courtroom. Evidence had to be tangible. Mather's conclusion remains an important lesson in American criminal procedure:

In his published sermon,

“Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits,”

Mather argued against the use of “spectral evidence” in the courtroom. Evidence had to be tangible. Mather's conclusion remains an important lesson in American criminal procedure:

“It is better that ten suspected witches should escape than that one innocent person should be condemned.”

Revulsion at the witch trials led to important legal reforms and expansion of the rights of the accused. Thus, Puritan theology inadvertently led to the development of important political and religious rights in America.

“The Protestant Reformers, and particularly the English and colonial Puritans, for all their zealous narrowness and for all their participation in intolerant episodes, still promulgated principles that sometimes led by implication beyond their own behavior: Every man his own priest; justification by faith; the Bible as the sole authority; the gathered, congregational, nonhierarchical, internally democratic church. These religious ideas had unintended social and political consequences – unintended and unwelcome to some; welcomed and explicitly affirmed by others,” William Lee Miller wrote in The First Liberty.

The most important lasting legacy of the Puritans, Haynes said, is government by constitution, which comes from the Puritans’ idea of covenant – forming a compact or a charter.

“We are a chartered people; we are not a tribe,” he said. “The idea of covenant in the 1600s was to become the idea of constitution in 1700s. It is a religious idea that became secular. In many ways we have the Puritans to thank for our Constitution. Unfortunately this history – and the legacy of Winthrop and Williams – is lost to most people.”

Morbid interest in the Puritans’ excesses tends to obscure their important contributions and ongoing influence on American society, Haynes contends.

“Most textbooks treat the Puritans as cartoon figures and stereotypes. The history books usually tell us how narrow–minded they were and just how ‘puritan’ they were; or, one of my favorite definitions, ’Puritanism is the haunting fear that someone somewhere might be happy.’ But the Puritans were not as dour as they are often depicted in textbooks. There was rum in the bottom of those ships; and they had sex, and they enjoyed it,” he said.

Haynes believes that in order for Americans to truly understand themselves, it is important to reach a balanced understanding of the Puritans.

“It is wrong to read through the lens of our stereotypes. It does us no good to demonize the Puritans because it hurts our self–understanding as a people,” he said. “The Puritans deeply shaped our culture. We are all heirs to their legacy, and we are all deeply influenced by the Puritans in many ways we don’t know. I think all Americans are Puritans in some ways. If we distort them, we will have trouble understanding ourselves today.”

After the 17th century, the Puritans evolved and faded into America’s increasingly diverse tapestry. But their strands remain deeply woven in American society.

“Their principles were to become long–lasting emphases in American church–life and theology not only because they were so effectively institutionalized in a region destined to wield major influence in a growing nation; but because, in a somewhat modified form, they were also perpetuated by contemporary Anglicans, Presbyterians, Baptists and even Quakers. They would become part of the westward–surging Methodist tide and make their way, as well, into many communions of continental heritage,” wrote Sydney E. Ahlstrom in Theology in America: A Historical Survey (Princeton University Press, 1961)

The downside of the Puritans’ legacy also remains deeply within the nation’s fabric, and is often expressed in certain forms of intolerance and fear of the “other,” which began with the hatred of Catholics, Haynes said.

“Every time the nation faces a serious crisis, you see this anxiety come to the surface,” he said. “A lot of the rhetoric that used to be directed against Catholics you can now hear about American Muslims – that they can never be good Americans because of what they believe.”

After the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the Rev. Jerry Falwell, along with televangelist Pat Robertson, blamed the devastation on atheists, abortionists, feminists, homosexuals, the American Civil Liberties Union and the People for the American Way.

“Jerry Falwell’s choice of words was so unfortunate; but if you go back to Winthrop’s language, you can see an old theme: ’If we live up to what we are to be and what God requires, we will prosper. If we fail to obey God, we will be destroyed,’” Haynes said. “Since Sept. 11, many people are afraid we’ve fallen away and should return. They believe we are losing ground because we have fallen away from the source of our liberty and who we are as a people.”

After the Civil War, many people similarly believed the devastation was caused by disobedience to God and a breach in the covenant.

“The Civil War was seen by many Americans as God’s judgment on America, and many people believed the appropriate response was to amend the Constitution to include God and Jesus Christ. This came close very close to passing. They felt the judgment of God on our nation had to be corrected, because of the great defect in the Constitution omitting God,” Haynes said.

During the Cold War, fear of atheistic communism prompted Congress to insert the phrase, “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance. Recently, with lawsuits aimed at removing the phrase, many fear the consequences if it is removed.

“Why should we care about prayer and the pledge? A strong segment of the population sees the United States as God–blessed nation; that our liberties are inseparably linked to God’s gift and his involvement in the American experiment. You don’t have freedom unless you acknowledge the God who gave it to you. And if you deal falsely with God, you will be destroyed,” Haynes said.

“Many Americans feel the Puritan anxiety of the removal of God’s blessing on America. This is a culture war issue in the deepest sense, because all could be lost. We need to have a perspective on these themes and realize how long we’ve been struggling with them and why they are so important to so many people,” he said.

‘Rogues’ Island’

In 1635, the General Court of Massachusetts found Roger Williams guilty of contempt and banished him from the colony. So Williams went next door to Rhode Island and founded Providence in 1636. Williams governed the colony under the mandate of religious liberty – “a haven for the cause of conscience.”

“Rhode Island was the first spot in human history where one’s standing in civic order was completely disconnected from one’s standing in religious community,” Haynes said. “At the time, people thought you couldn’t set up a society without an established religion. Williams opened up the proverbial Pandora’s box.”

Rhode Island became popularly known as “Rogue’s Island,” because it attracted so many misfits, Martin Marty wrote in Pilgrims in Their Own Land. The colony also became a haven for Quakers and Catholics – the most controversial and hated religious groups in the colonies at the time. Williams was not fond of either, but he insisted they must be allowed – and not merely tolerated, but given complete free exercise.

“Among the people who came [to Rhode Island], the Quakers pushed even Williams to the limits of tolerance,“ Marty wrote. “Always the Quakers kept nettling Williams, but he defended their right to propagate their views.”

Williams believed free exercise was God’s mandate, and he advocated free exercise on theological grounds. “Williams argued that God required it,” Haynes said. “Even if you didn’t want Catholics and Quakers in your mix, you had to do it. Williams proclaimed, ‘Here is a haven for the cause of conscience, not the sewer of New England.’”

In 1654, the first group of Jews to come to North America arrived in New Amsterdam (later to become New York). The governor, Peter Stuyvesant, was hostile toward the émigrés and forced them into ghettoes. Four years later, another group of Jews arrived in Rhode Island. Williams granted them free exercise and spared them persecution.

“The treatment of Jews is a test in particular for a person who held intensely to the truth of the Christian revelation, as Williams did, at the time, and among the folk with whom he lived, when religious beliefs were taken as seriously as some economic, political and scientific beliefs are taken now,” William Lee Miller wrote.

In an age when Jews were subject to mass expulsions, pogroms and other forms of oppression, most synagogues were designed with trap doors for quick escape. But the Jews of Rhode Island were never forced into such a precarious situation – a fact Haynes said is important to remember in the current political atmosphere in the world.

“Yes, we have a long way to go in the U.S.; but despite all of our faults and problems, here is something to think about: The Jews have never had to use that trap door. ... That is who we are at our best. That is why I think the First Amendment is America’s greatest gift to world civilization; and that is the legacy of Roger Williams,” Haynes said.

From Winthrop & Williams to the Tea Party

The role of religion in public life and the notion of pluralism – and just how much of it we can tolerate – were critical issues 400 years ago just as they are today.

An explanation of the origins of religious liberty in America could begin at many places, most obviously with the Founders – Jefferson and Madison in particular. Benjamin Franklin had much to say about religion and public life, and he offers a case study of an exemplary citizen who set the blueprint for what it is to be an American.

“Benjamin Franklin was such an archetypical American, and he was

the father of the country in so many ways,” Haynes said. “His

way of thinking about his life, his transformation, and his melding of

the Puritan way of thinking with the Enlightenment really set the stage.”

“Benjamin Franklin was such an archetypical American, and he was

the father of the country in so many ways,” Haynes said. “His

way of thinking about his life, his transformation, and his melding of

the Puritan way of thinking with the Enlightenment really set the stage.”

But the origins go even further back to the two conflicting visions of the “city on a hill” as embodied by Winthrop and Williams. They are enduring archetypes to this day.

“These two visions of America continue to shape and frame the debate,” Haynes said. “In our society, we are deeply struggling about how to deal with religion in public life in the most religiously diverse nation in the world. We really have to deal with these conflicts honestly and find out where they come from.”

The first chapter of American history — the Winthrop-Williams debate in particular — is the logical place to start.

“If you think religious liberty is difficult and complicated, blame Roger Williams, because it starts with Williams in Rhode Island,” Haynes said. “That is the genius of the American experience – never use the engine of government to deny people the freedom to choose in matters of faith – Williams thought this was the way. Our public square ought to be just like this.”