Confronting torture

Panel focuses on ‘enhanced interrogation methods’; executive authority

‘Extraordinary measures’

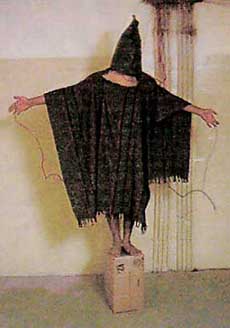

The raging national debate over torture and the legal basis provided for the Bush administration’s harsh interrogation tactics reached ground zero at Chapman University during a forum entitled “Presidential Power and Success in Times of Crisis.”

Chapman visiting law professor John Yoo, who has gained notoriety for his co-authorship of the so-called “torture memos” written for the Bush administration, defended his legal reasoning at the forum, April 21, 2009. (See video recording here.)

Yoo faced harsh criticism from his law school colleagues and numerous protesters in the audience and outside the auditorium. Several people in the audience jeered Yoo – one calling him a war criminal, and another calling for his arrest.

Speaking on a four-person panel, Chapman Law School Dean John Eastman defended Yoo, while Chapman law professors Katherine Darmer and Lawrence Rosenthal assailed Yoo’s legal reasoning.

Yoo opened the panel discussion by defending his positions on several bases – the extraordinary situation of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the constitutional authority of the president and historical precedent, as he interprets it.

“We are in a state of war with Al Qaeda terrorists,” Yoo began. “What if the Soviet Union had carried out the same attacks? Would there be any doubt we are in a state of war?”

Yoo said much of the current criticism against him comes with the benefit of hindsight, and absent the emergency situation immediately following the Sept. 11 attacks.

“Things look very different now than they did in 2001-2002,” he said. “That [situation] forced us to consider extraordinary measures.”

Those measures included coercive interrogation techniques against suspected terrorists, searches and seizures of suspected terrorists, and the aggressive assertion of presidential authority to carry out such measures. The legal rationale for these measures are outlined in a series of memos written by Yoo and his former boss, Jay Bybee, at the Office of Legal Counsel (a division of the Department of Justice) in 2001 and 2002.

In the heat of the moment

Katherine Darmer and Lawrence Rosenthal said the Sept. 11 attacks and the subsequent “war on terror” cannot be used as a catch-all excuse for overarching legal opinions or misguided presidential actions.

“We have to be careful not to judge a decision in the heat of the moment,” Darmer noted, “but it is clear the position endorsed in these memos is still being endorsed by Professor Yoo years later. It is no longer a decision in the heat of the moment.”

“We have to be careful not to judge a decision in the heat of the moment,” Darmer noted, “but it is clear the position endorsed in these memos is still being endorsed by Professor Yoo years later. It is no longer a decision in the heat of the moment.”

The bottom line, Darmer said: The Office of Legal Counsel – with Yoo and Bybee as its principal legal authors – provided the legal justification for an unconstitutional policy.

“The Office of Legal Counsel provided legal cover for torture,” she said.

Yoo’s bottom line: The actions taken, based in his recommendations, helped prevent further attacks on U.S. soil.

“Was it worth it?” Yoo asked, referring to the tide of reproach he has received for his positions. “We haven’t had an attack in more than seven years.” — At that, Yoo received applause.

‘Extreme acts’

“We conclude that torture as defined in and proscribed by Sections 2340 covers only extreme acts.”

— Jay S. Bybee, former assistant attorney general in charge of the Office of Legal Counsel at the Justice Department, Aug. 1, 2002

The Obama administration has released a series of memos from the Bush era, among them an Aug. 1, 2002, memo written by Jay S. Bybee, former chief of the Office of Legal Counsel and now a now a federal judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. In the memo, Bybee argues in favor of broad executive authority to carry out interrogations and a narrow legal definition of torture. In other words, only the most severe techniques should be considered torture, and therefore the administration had broad latitude to carry out such measures without violating the torture ban.

“These statutes suggest that ‘severe pain, as used in Section 2340, must rise to a similarly high level – the level that would ordinarily be associated with a sufficiently serious physical condition or injury such as death, organ failure or serious impairment of bodily functions – in order to constitute torture,” Bybee wrote.

Bybee’s memo has drawn a storm of criticism since its release. Even the Bush administration rejected its conclusions as far back as 2005, according to another Justice Department memo released by the Obama administration.

“The federal prohibition on torture is constitutional, and I believe it does apply as a general matter to the subject of detention and interrogation of detainees conducted pursuant to the President’s Commander in Chief authority. The statement to the contrary from the August 1, 2002, memorandum, quoted above, has been withdrawn and superseded, along with the entirety of the memorandum,” wrote Steven G. Bradbury of the Office of Legal Counsel in 2005.

Rosenthal chided Yoo and Eastman for continuing to defend many of the conclusions in the memos, when even the Bush administration had abandoned the positions.

“It seems like professors Yoo and Eastman are the only ones still holding these views,” Rosenthal said. “At the very minimum, Professor Yoo owed his client [President Bush] an opinion that could withstand scrutiny.”

Torturing the law

Getting Medieval in the Renaissance: Facsimile of a Woodcut in J. Damhoudère's Praxis Rerum Criminalium, Antwerp, 1556.

Getting Medieval in the Renaissance: Facsimile of a Woodcut in J. Damhoudère's Praxis Rerum Criminalium, Antwerp, 1556. “Severe mental pain or suffering means the prolonged mental harm caused by or resulting from the intentional infliction or threatened infliction of severe physical pain or suffering …”

— Title 18, United States Code § 2340

Eastman said a reading of the U.S. statute on torture and the United Nations Convention Against Torture does not present a clear definition of exactly what techniques constitute torture.

“Waterboarding is not clearly illegal,” Eastman said. “‘Severe mental pain and suffering’ and ‘prolonged mental harm’ are not clearly spelled out.”

Darmer and Rosenthal rejected this argument, saying waterboarding clearly constitutes torture, and is illegal under U.S. and international law.

“The morality and ethicality of the positions taken by Professor Yoo are a profound threat to the rule of law,” Rosenthal said.

Yoo and Eastman poked at “the lawyers” who would obstruct the apprehension of terrorists in their zeal to protect the rights of suspects.

“If you completely rule out coercive tactics … that is to say, ‘I am unwilling to do anything but read your Miranda rights and wait for the lawyer to show up,'” Yoo said. “I’m afraid these kinds of arguments return us to the overlawyered, timid approach to fighting terrorists.”

Eastman added, “This war has been more vetted by lawyers than any in history.”

Does torture work?

– Lawrence Rosenthal, Professor of Law, Chapman University

Recently released Justice Department memos show that the CIA subjected professed Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed to waterboarding 183 times, and Al Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah was waterboarded 83 times.

Defending CIA tactics on the Sunday morning news shows, former CIA Director Michael Hayden said these “enhanced interrogation techniques” yielded substantial information about Al Qaeda and its operations.

“The CIA claims their techniques work – big surprise there,” Rosenthal quipped.

More often, Darmer said, people subjected to torture will say anything – true or false – just to stop the abuse.

“These tactics led us on wild goose chases when people respond in pain,” Darmer said. “Have these tactics made us safer? They have not, and they have reduced our stature in the world. Even if it is established that torture works, we should make a moral choice to reject it.”

What if a terrorist is about to explode a nuclear bomb in a major city, and authorities have a suspect in custody? Wouldn’t it be proper to gain information, by any means necessary, to save lives?

Rosenthal said the “ticking time-bomb” argument is often misused in order to justify torture.

“You can’t rule out coercive techniques if you have a ticking time bomb, and there is a reasonable allowance for that. But Yoo goes grossly beyond that,” Rosenthal said.

Executive authority

“The President shall be commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States … He shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed.”

— United States Constitution, Article II, Sections 2 and 3

Two provisions of the Constitution – one designating the President “commander in chief” and the other assigning the President to “faithfully execute” the laws – were the source of dueling claims among the panelists: One side stressed the President’s powers as commander in chief, while the other side stressed the President’s responsibility to faithfully execute the laws.

Yoo said the nation’s Founders created a strong presidency specifically to respond quickly to national emergencies such as wars and attacks on U.S. soil. The president’s highest constitutional duty is to protect the nation against an attack; and in such an event, the president should “act with swiftness, secrecy and decision,” Yoo said.

Yoo cited the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863, as prime example of executive authority in action. “Lincoln acted under his own authority. Congress had its own version [of an emancipation law], but Lincoln acted as commander-in-chief,” Yoo said.

Yoo cited Lincoln’s predecessor, James Buchanan, is an example of an indecisive president who did not use his executive authority when he should have. “Buchanan believed secession was unconstitutional, but he did not believe he had the authority to stop it,” Yoo said.

Darmer said Yoo’s comparison between the Civil War and the “War on Terror” was invalid. “There is an enormous difference between using executive power to free the slaves and to torture,” she said.

Power to the President

“An act of the Legislature repugnant to the Constitution is void.”

— Justice John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, 1803

Former President George W. Bush frequently claimed that Congress transgressed on his Constitutional authority as commander in chief. In lieu exercising his veto power, Bush most often issued “signing statements” – legal documents in which the president set aside portions of laws passed by Congress. The practice was highly controversial, particularly one signing statement in which the president opted out of Congress’s ban on torture.

In supporting such presidential action, Yoo cited the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison (1803), which solidified the principle that Congress cannot enact laws that conflict with the Constitution. Therefore, the President is not obliged to comply with Congressional action he believes conflicts with his constitutional authority, according to Yoo.

“The Supreme Court says no branch of government has to obey an unconstitutional law,” Yoo said.

Following this logic, if the president believed Congress’s torture ban was an unconstitutional transgression on his authority as commander-in-chief, he would not have to follow the law.

John Eastman supported this view: “If a statute impedes on the president’s power as commander-in-chief, then it is an unconstitutional intrusion on his power.”

President Franklin Roosevelt, for example, before America’s entry into World War II, “violated neutrality laws left and right,” Eastman said. “The law was unconstitutional, not the president’s actions.”

Darmer and Rosenthal countered that the president cannot simply disregard Congress or ignore a law he does not like. In doing so, the president places himself above the law, or in former President Nixon’s parlance, “If the president does it, then it’s not illegal.”

“The notion that the president is not limited by law is extraordinary,” Darmer said. “The president is not above the law. Even if torture is effective, the president is still bound by the Constitution. Torture is illegal, and it’s also wrong.”

Secure in their persons?

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated …”

— The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution

In addition to his opinions on presidential authority and interrogations, Yoo’s views on searches and seizures have generated heated controversy. In his Oct. 23, 2001 memo to the Attorney General, Yoo states that the Fourth Amendment should not apply to domestic military efforts to capture terrorists.

“In light of the well-settled understanding that constitutional constraints must give way in some respects to the exigencies of war, we think that the better view is that the Fourth Amendment does not apply to domestic military operations designed to deter and prevent further terrorist attacks,” Yoo wrote.

Rosenthal said Yoo’s reasoning went far beyond what is constitutional. “As long as the military thinks it is looking for a terrorist, it can raid anyone’s home,” Rosenthal said, summarizing his reading of the memo. “The Fourth Amendment is jettisoned when it comes to searching for terrorists.”

Finding accountability

– Katherine Darmer

Darmer and Rosenthal called for an independent investigation into the activities of the Office of Legal Counsel.

“We need more facts; we need an investigation; and we need to learn from mistakes to avoid making them again,” Darmer said.

Despite her disagreement with Yoo’s legal opinions, Darmer cautioned against vilifying Yoo, particularly since he was not responsible for executing his legal recommendations, nor was he in charge of the Office of Legal Counsel.

“Yoo was a subordinate of Jay Bybee, so it is important not to scapegoat Professor Yoo,” she said.

Further reading

Not fit to teach

Lawrence Rosenthal assails John Yoo’s competence in this April 9, 2009, Los Angeles Times column.

Defending Yoo

John Eastman defends numerous details of John Yoo’s legal memos in an April 9, 2009 column in the Los Angeles Times.

Judging John Yoo

Editorial asks if Yoo should be held legally responsible for the actions of others who relied on his legal reasoning.

See more resources and readings on torture, and official documents here.

Where are they now?

John Yoo enjoys job security

Yoo settles back into his tenured position at Berkeley's Boalt Hall.

John Eastman eschews job security

Eastman quits job as law school dean to run for attorney general.

‘An original thinker’

“Eastman also brings intriguing credentials. He is an original thinker and constitutional scholar. He presents new ideas for how to organize and direct the attorney general's office, and he amassed an impressive record as Chapman's dean.”